No matter your war, your story mattered

This week marks 100 years since Australian’s first landed in Gallipoli, and our nation pauses to commemorate the legacy of war.

Growing up I always felt a little lost at ANZAC Day amongst the flag waving and medal wearing grandkids and adults honouring those who lost their lives at war.

Sure, there were vague family stories. My great, great, great Uncle was a bugler in WWII, and Great Uncle Allan, a humble barber from Warrnambool was a POW at Kanchanburi in Thailand. But in my innocence, they weren’t true ANZACS whose legends remained mythical. They were the support act while we waited for the stars to step on stage. I hang my head my head in shame now when I think of how many chapters I may have skimmed over in the history books at school in my eagerness to get to the ANZAC vignettes.

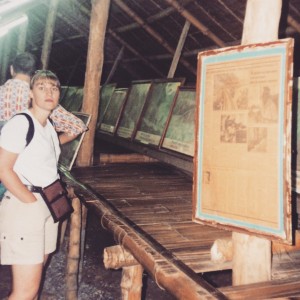

Years later as an adult I trekked those wretched POW zones in Kanchanburi, those fields of beautiful silence in France, and across shrouds of pine needles in the eroding trenches at Gallipoli. I came to quickly appreciate that whether you were an ANZAC or not, you were a bloody hero to have survived a milli-second of war time hell.

Every one of those Australians who went to war had a story to tell, a story to survive for. Every family member and loved one they left behind, or returned to have a chapter to write in the history books. Whether an ANZAC or not, we really are commemorating them all this April 25th, 2015.

Making sense of war through literature

The narrative of war is a difficult subject to navigate with your kids. As a mum, and an avid book worm I reckon literature is both consoling and connecting when trying to make sense of the world, and to find some sense of peace while focussing on the subject of war.

I have a 7 and 10 year old. Curious peeps they are and the ANZAC Centenary has certainly been topical at school and in the media in recent weeks.

Explaining conscription, conditions and commemorations of the war dead to your child is a rather uncomfortable experience.

Hell, I should’ve been sponsored by Kleenex in my attempts to explain it all – that would’ve sorted out the High school excursion fees to Gallipoli in years to come.

But with the ANZAC commemoration in mind I turned to books to help me present the grimness of Gallipoli, to honour the ghosts and to shake my head in sadness for the ‘glorious dead’.

Here’s 7 storybooks I’ve used to look at our ANZAC history and Australian war experiences:

- A Day to Remember by Jacki French

- Anzac Biscuits by Phil Cummings

- An Anzac Tale by Ruth Starke

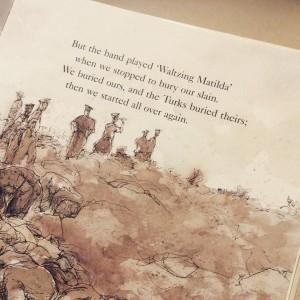

- And the band played Waltzing Matilda by Eric Bogle

- Simpson and his Donkey by Mark Greenwood

- The Anzac puppy by Peter Millett

- Evan’s Gallipoli by Kerry Greenwood

Here’s my Gallipoli story

There’s a unifying sense of gratitude, grief, coming of age and sadness when we talk of war. There’s also a mighty drive to stand in places of conflict to ponder mistakes, lessons and the futility of battle.

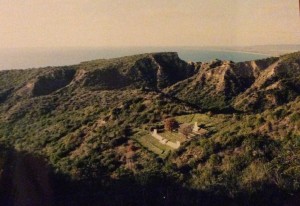

I’ve been to Gallipoli – I’ve walked those beaches in my warm thermals, with a full belly, and no gruesome images to shy away from. I’ve written respectfully emotional accounts in a well travelled journal. I remember recalling that Gallipoli would be a very peaceful peninsula if it weren’t for the gruesome history fertilising its beauty.

It was hard to conceive that this was once a muddy, bloody landscape strewn with bodies left to decay where they fell – this was now a ‘must visit’ stamp in my life adventures.

8, 7009 Australians lost their lives in Gallipoli. A fraction of the casualties when you consider the mortality rate of Turkey who mourned the deaths of over 70, 000 Turkish men lost . On all sides, it was a sea of dead, and I’d crossed many seas to learn the stories of sacrifice, duty and unspoken horrors of Galllipoli.

As I reach for my January 2003 diary a brittle leaf falls from its pages. I recall watching it gently fall into a trench I was standing in near Chunuk Bair. The leaf fell gently and with grace. Such movement was not afforded the men who once fell in these trenches.

With rawness 12 years ago I wrote:

In 1915 our countrymen stepped onto these shores, as wide-eyed and awestruck by overseas adventures as we are today. They shot with rifles while we shoot with cameras. Their blood fertilises the soil we walk on with reverence today. “

Later we visit the Kabatepe Museum which has me struggling:-

“We wander past glass cabinets and exhibits in this tomb-like museum. Our Turkish hosts nods gravely behind us, ever respectful of our pilgrimage, while we become uncomfortably more aware of the significance of Gallipoli to the Turks as well. I look at a photo of John Simpson, gazing with pride astride his donkey. A wounded passenger by his side. One day later both were dead. I move on to an ankle bone, mummified and embedded in a worn, torn boot. Next to it lies a skull, with a neat bullet wedged into the forehead

I step outside to gather gobfuls of air. The reality of Gallipoli presses on my shoulders and deep down into my gut. This isn’t sacrifice for King and Country, it’s more mate and memory. Pines lean into the wind, listening for the distant keening of mourning mothers.”

Understanding our history

The ghosts of men lost and the memories never fade. Don’t get me wrong, I loathe the concept of war itself. It was, and is merciless. The battle cries and spoils of victory don’t sit well with me. But I recognise that Gallipoli may well have witnessed the birth of larrikinism.

That Gallipoli was a coming of age story for Australia, and New Zealand and that there is a heroism in survival as much as in death. Visiting sites and memorials and reading books helps us make sense of our own sense of national identify

I had a quiet moment in 2003 at Gallipoli’s Beach Cemetery at the grave of John Simpson and placed a toothpick Aussie flag at its base, patting the stone in reverence.

Years later I hear my two children recount the tale of the heroics of Simpson and his donkey.

This is a story to them. And yet it is a connection.

I show them my photo and we talk about memories, travel, learning about yourself and learning about your history. Some of this they will not understand till they themselves are grown and exploring their own sense of identity.

Here’s a few ways we’ve reflected on 100 years of Gallipoli:-

- We looked at an on-line catalogue of images by famous Australian artist Sydney Nolan of artworks such as ‘The Lost Brother’ and ‘Gallipoli Riders’

- We bought a poppy and an ANZAC badge

- We completed the activity sheets in the Gallipoli bags distributed to school kids by the RSL – loved these!

- We checked out the ANZAC Day memorial website

- We watch Sam Neill’s ABC Documentary “Why Anzac” as he ponders “why ANZAC itself has such a hold on our imagination”.

- I show my kids my travel diary and photos

Reading kids books helps make sense of history:

I share these stories and others to help my children understand our history and our sense of peace. Heck I hope to understand a little more of it myself.

War is distressing. War creates grief and gaps in families and in futures.

I certainly don’t want them to think war is an option. I want them to see my tears and hear my sighs as I read books and speak of places I’ve seen, and tombs I have stood before.

These books and others, so artfully presented by talented authors and artists can help my children understand our history and gain a glimpse into the price of war

Our ANZAC heritage is important, and more importantly so is our sense of peace. Turning the pages can help us bring our past to life. Because lest we forget.

Check out this great article on kids literature and the ANZACS

Check out this lovely youtube narration of the Simpson and His Donkey by Mark Greenwood